As of this month, over 4,000 Americans are on the waiting list to receive a heart transplant. With failing hearts, these patients have no other options; heart tissue, unlike other parts of the body, is unable to heal itself once it is damaged.

As of this month, over 4,000 Americans are on the waiting list to receive a heart transplant. With failing hearts, these patients have no other options; heart tissue, unlike other parts of the body, is unable to heal itself once it is damaged.

But recent work by a group at Carnegie Mellon could one day lead to a world in which transplants are no longer necessary to repair damaged organs.

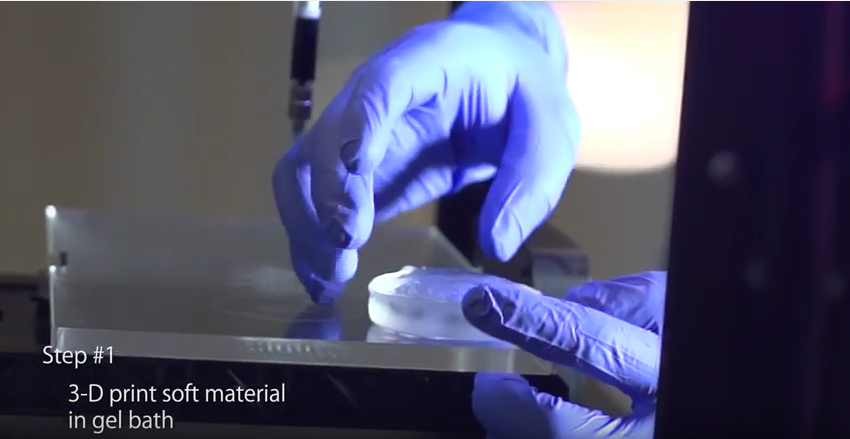

"We've been able to take MRI images of coronary arteries and 3-D images of embryonic hearts and 3-D bioprint them with unprecedented resolution and quality out of very soft materials like collagens, alginates and fibrins," said Adam Feinberg, an associate professor of Materials Science and Engineering and Biomedical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University.

Feinberg leads the Regenerative Biomaterials and Therapeutics Group, and the group's study was published in the October 23 issue of the journal Science Advances. A demonstration of the technology can be viewed online.

"As excellently demonstrated by Professor Feinberg's work in bioprinting, our CMU researchers continue to develop novel solutions like this for problems that can have a transformational effect on society," said Jim Garrett, Dean of Carnegie Mellon's College of Engineering. "We should expect to see 3-D bioprinting continue to grow as an important tool for a large number of medical applications."

Traditional 3-D printers build hard objects typically made of plastic or metal, and they work by depositing material onto a surface layer-by-layer to create the 3-D object. Printing each layer requires sturdy support from the layers below, so printing with soft materials like gels has been limited.

"3-D printing of various materials has been a common trend in tissue engineering in the last decade, but until now, no one had developed a method for assembling common tissue engineering gels like collagen or fibrin," said TJ Hinton, a graduate student in biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon and lead author of the study.

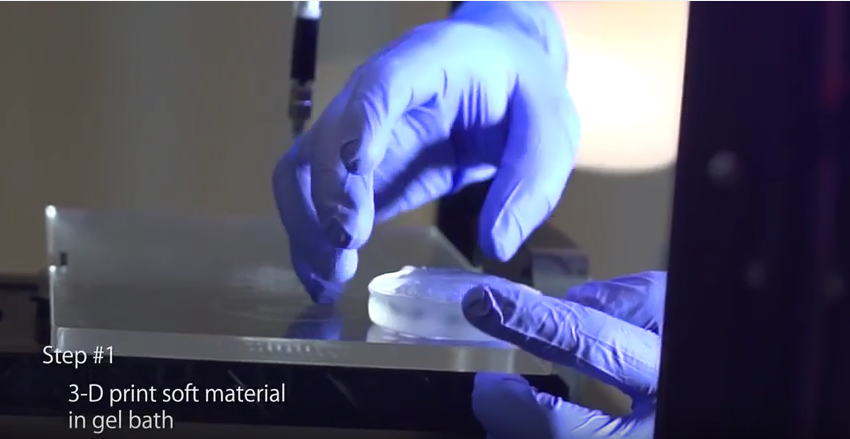

"The challenge with soft materials — think about something like Jello that we eat — is that they collapse under their own weight when 3-D printed in air," explained Feinberg. "So we developed a method of printing these soft materials inside a support bath material. Essentially, we print one gel inside of another gel, which allows us to accurately position the soft material as it's being printed, layer-by-layer."

One of the major advances of this technique, termed FRESH, or "Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels," is that the support gel can be easily melted away and removed by heating to body temperature, which does not damage the delicate biological molecules or living cells that were bioprinted. As a next step, the group is working towards incorporating real heart cells into these 3-D printed tissue structures, providing a scaffold to help form contractile muscle.

Bioprinting is a growing field, but to date, most 3-D bioprinters have cost over $100,000 and/or require specialized expertise to operate, limiting wider-spread adoption.